What Should Be Included in the Money Supply

We have come across a few articles discussing money and credit recently, and want to add our two cents. Before we begin, we want to briefly discuss the definition of money.

It is useful to have a fairly strict definition of the general medium of exchange. That helps one to avoid confusing money with e.g. credit instruments. The definition set forth by Rothbard (in the monograph 'Austrian Definitions of the Supply of Money'), which follows the guidelines laid down by Mises in the 'Theory of Money and Credit' is as follows:

"Money is the general medium of exchange, the thing that all other goods and services are traded for, the final payment for such goods on the market."

Armed with this definition, one can determine what should considered part of the money supply in the narrow and broader sense. In the modern-day fiat money system, standard money consists of banknotes and coins, i.e., currency. These banknotes once used to be receipts redeemable for definite quantities of the market-chosen metallic money (gold and/or silver), but were over time deprived of this character by government intervention. It should be pointed out that declaring that something is legal tender is not enough to make that something into money. Unless the money concerned is widely accepted in exchange, such a declaration won't suffice. However, the state-issued scrip is also the only type of money accepted in payment of taxes, which creates strong demand for it. Furthermore, the gradual manner in which gold was replaced by fiat money contributed greatly to the latter's acceptance by market actors. However, we don't want to discuss the merits of gold as money here or the historical developments that have led to the adoption of fiat money, but rather what money currently is.

In addition to standard money (notes and coins) there are money substitutes (deposit money) which can be exchanged for standard money on demand. Some of these are covered money subs! titutes, which means that bank reserves held with the central bank exist with respect to them. The remainder are 'uncovered' money substitutes, also known as fiduciary media. These likewise confer a claim to standard money to deposit holders, but they are not covered by bank reserves (therefore bank customers need 'fiducia' – trust – that they will indeed be paid on demand).

In practice, these three types of money (standard money, covered and uncovered money substitutes) together form the money supply, as they are all generally accepted as final payment for goods and services.

The broad Austrian money supply measure TMS-2 is constructed based on this definition (there is a narrower money supply measure TMS-1 which excludes savings deposits; although savings deposits are generally available on demand in the US, it makes sense for analytical purposes to observe the narrower measure as well, as it is subject to more frequent turnover). The measure therefore excludes e.g. money market funds, because including them would amount to double-counting. If one buys units in a money market fund, the fund employs one's money in turn to buy commercial paper or other short term debt instruments such as t-bills. The money will move into someone else's account and thus be reflected in total outstanding bank deposits. While it is very easy to cash in money market fund units, they cannot be used directly in payment – they must first be sold for money.

A complete list of what is included in the TMS measures as well as other money supply measures, including a more extensive discussion of the topic and links to various useful references can be found here: "Money Supply Metrics, the Austrian Take", by Michael Pollaro.

As a general remark, we are referring specifically to the US banking system and the dollar money supply in this article. In other countries, both commercial banking practices and the modus operandi of central banks are not exactly the same as in the US, even th! ough all ! modern fiat money systems are quite similar in their basic outlines (as an example: in many countries, 'savings deposits' refer only to money that is in time deposits and hence is not available on demand).

Measuring Money in New Ways?

One of the articles we have recently come across is "Monetary Inflation Prospects" by Alastair Macleod. Mr. Macleod attempts to 'quantify the prospects for inflation', this is to say, the prospects of money losing a lot of its purchasing power at some point in the future (as expressed by a noticeable rise in CPI or similar official index numbers). There is in principle nothing wrong with watching the growth rate of the money supply in order to get an idea whether a large future loss of the purchasing power of the money concerned can be expected, even though that is not necessarily the most pernicious effect of monetary inflation. That dubious distinction belongs to the fact that monetary inflation tends to distort relative prices in the economy. This distortion upsets economic calculation and leads to malinvestment of scarce capital, which is the central feature of the boom-bust cycle.

Mr. Macleod is however mainly interested in finding out what the dangers for money's objective exchange value, i.e., its overall purchasing power, are. For this purpose he has constructed yet another measure of the money supply, which he calls the 'Fiat Money Quantity', or FQM for short. He defines it as follows:

"The FMQ is comprised of the sum of cash and coin, plus all accessible deposits, plus our bank's deposits held at the central bank."

However, adding up these magnitudes makes actually no sense – the deposits held by banks at the central bank cannot be counted as part of the money supply. Although these bank reserves represent the cash assets of banks, they are mirrored by covered money substitutes in the form of deposit money on the liability side of bank balance sheets.

Imagine that a bank that has just run out of vault ca! sh is fac! ed with a withdrawal demand from a customer who wants to exchange his deposit money for currency. In that case, the bank would ask the Fed to transform part of its reserves into cash currency and then hand it over to the customer. Both the bank's reserves at the Fed and the customer's deposit at the bank would be drawn down by a similar amount, while currency in circulation would increase by the same amount as well. The commercial bank's balance sheet would shrink and so would bank reserves deposited at the Fed, but the amount of money in the economy would remain the same (incidentally, from the point of view of the Fed, merely the composition of its liabilities would be altered).

It should be noted here that in the US monetary system, for many years bank reserves have only been very loosely connected with the money supply. A decisive change took place when sweeps were introduced in the mid 1990s. These allow banks to sweep unused money held in demand deposits into so-called money market deposit accounts overnight. Once there, said money masquerades as savings deposits, which are not subject to reserve requirements. This is why it was possible for the money supply to expand markedly from the mid 1990s onward without bank reserves growing concurrently. Conversely, the massive rise in bank reserves due to 'QE' since the 2008 crisis has not led to a proportional expansion in money and credit (i.e., the type of expansion that would theoretically have been possible by applying the 'reserves multiplier').

Shadow Banking and Credit Expansion

This brings us to another article which we have become aware of due to a missive about the 'shadow banking' sector published at Zerohedge. It starts out by noting that there are complaints that the Fed's QE operations have deprived the so-called shadow banking system of 'high quality collateral'. However, this immediately raises the question: relative to when?

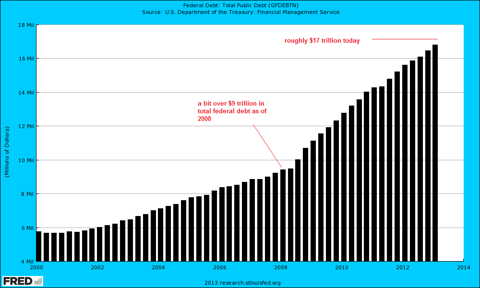

After all, the supply of federal debt has increased by roughly $8 trillion since 2008 when! QE was f! irst started (total federal debt has grown from about $9 trillion in 2008 to $17 trillion today. Due to the unresolved debt ceiling debate the official number has been 'stuck' at a level below $17 trillion for a while now, but it will immediately rise to that point once the new 'ceiling' has been negotiated).

As Ramsey Su has pointed out in these pages, the Fed is on track to buy up nearly all new issuance in the mortgage credit space this year, but even so there is a vast stock of outstanding agency debt of which the Fed holds only slightly over $60 billion these days. For all intents and purposes, agency debt is nearly equal to federal debt. Ginnie Mae's debt has always been federally guaranteed, while Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac debt is de facto federally guaranteed ever since these entities have entered 'conservatorship'. For an overview of the amounts involved see here.

(click to enlarge)

Even though the Fed has bought a large amount of existing treasury debt, even more new debt has been issued by the government - click to enlarge.

As a general comment on this: we do not believe that the shrinking of the shadow banking system's overall balance sheet has much to do with a lack of collateral. It has probably far more to do with new regulations regarding bank capital and leverage ratios, as well as the limits placed on the proprietary trading operations of banks. Since banks have for instance sharply reduced their inventory of corporate bonds and are no longer the active market makers they once were, there is less collateral traffic overall. Moreover, the crisis has bankrupted a number of banks and other players in the shadow banking industry, leading to a commensurate decline in the associated portfolios. Some of these portfolios contained inter alia large amounts of synthetic securities. Such synthetics like e.g. CDS contracts require the posting of acceptable collateral fo! r margin ! purposes.. Consider in this context that the CDS market on sovereign debt in the euro area has been virtually 'killed' by government fiat.

We would generally agree though that financial innovation leads to 'a lowering of the demand for money', 'financial deepening' and 'supports financial globalization', as the IMF's Manmohan Singh wrote with regard to the topic.

The article at Zerohedge is referencing an article by one Peter Stella, "Exit Path Implications for Collateral Chains". Although Mr. Stella is well informed regarding the technicalities surrounding QE, he comes to a number of conclusions that strike us as downright absurd.

At one point Mr. Stella implies that something is very different about money and credit creation in modern times as opposed to how it was done previously:

"When it comes to reducing excess reserves, the 'how' matters as much as the 'when' and 'how much'. Understanding this point requires mastery of the brave new world of shadow banks and re-hypothecation – a world that either did not exist or was truly in the shadows when most of us were taught about money and credit creation."

We can hereby reassure 'most of us' in at least one respect: the existence of the shadow banking system has not changed the process of money creation in the slightest. It has led to more intensive credit intermediation, especially credit intermediation directly connected to trading in financial markets (in a way it can be regarded as a symptom of the increasing financialization of the economy), but money is still created the same way as prior to the ascendance of the shadow banking system. Before we get to the details, let us look at a few more points Mr. Stella makes:

"If Rip Van Winkle awoke today after a five-year nap, he would see only one key development in the Fed's balance sheet – securities holdings higher by $2.9 trillion and deposits of depository institutions (banks) higher by $ 2.2 trillion.

If he asked how this happen! ed, Rip wo! uld be given a very simple answer.

The Fed bought securities to lower interest rates; it paid for them by creating bank reserves.

That is, the Fed credited the securities seller's commercial bank with a deposit at one of the 12 Federal Reserve Banks, and the commercial bank then credited the seller's account. On net, privately held securities were exchanged for Fed deposits.

If pressed further as to why banks are holding enormous reserves at the Fed, Rip would get an equally simple answer: Banks have no choice.

It is – for all intents and purposes – technically and legally impossible for a bank to transfer deposits at a Federal Reserve Bank to a nonbank.

Reserves in the US are defined to comprise bank deposits held at one of the 12 Federal Reserve Banks (plus qualifying vault cash).

Fed deposits may be transferred only to entities entitled to hold Fed accounts.

This is a key point when thinking about the various exit paths ahead. Fed deposits are not fungible outside the banking system, but Treasuries are.

(emphasis added)

Now, all of this is technically correct, except that the amount of money in the economy has actually increased by nearly twice as much (it appears to us that Stella errs with regard to the size of the money supply in 2008, judging from the accompanying chart; possibly because he double counts by including certain credit instruments).

Mr. Stella then writes:

"The stock of marketable, highly liquid, AA+ collateral fell by trillions (disappearing into the Fed's portfolio, i.e. System Open Market Account).

The stock of assets available only for interbank trade (bank reserve deposits at the Fed) rose by trillions."

(emphasis in original)

This is also technically correct, but once again, it is a big so what in light of the fact that the funded debt issued by the US treasury has likewise increased by trillions over the same stretch. Mr. Stella then implies that a 'lack of collateral' due to Q! E represe! nts an obstacle to credit creation by banks and non-banks alike. First of all, non-banks cannot create credit ex nihilo anyway – they can only act as credit intermediaries. Secondly, here is what this alleged 'lack of collateral' actually looks like in reality:

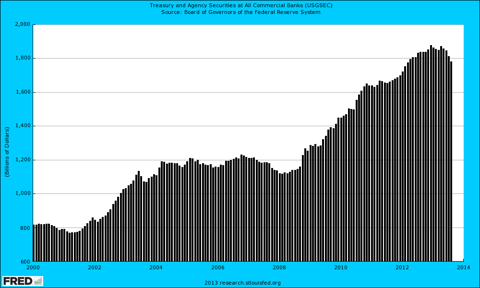

(click to enlarge)

Treasury and agency securities held by US commercial banks: up by more than 50% since 2008. What lack of collateral? - click to enlarge.

Banks have monetized a lot of treasury debt since 2008, mainly because private sector credit demand has waned (especially on the part of households; the same is not true for corporations) and because their own balance sheets are still hiding a lot of skeletons that they are currently not required to mark to market. Moreover, banks are no doubt mindful of the new regulations regarding capital requirements and bank leverage ratios that are being introduced.

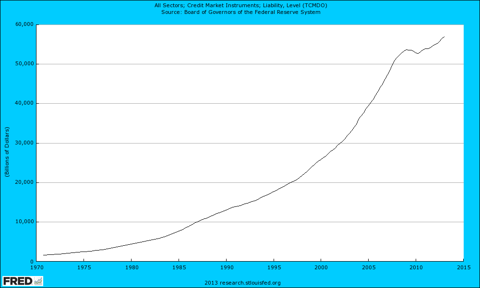

Given that corporate bond issuance of every quality has also risen to a record high (by leaps and bounds), we ask again, where exactly is this shortage of collateral? As an aside, if one worries about a lack of credit growth one should occasionally consult the chart of total US credit market debt owed, which after a brief interruption in 2008/9 has soared to a new record high – at a pace far exceeding the growth in economic output:

(click to enlarge)

Total US credit market debt owed is currently at a new record high of $57 trillion - click to enlarge.

Mr. Stella is quite correct that the level of bank reserves represents neither a constraint to bank lending nor an inducement to increase bank lending (and that banks have no control over the level of reserves) – see also our comment on the extremely loose (de facto non-existent) connection bet! ween rese! rves and the money supply above. We have seen some writers complain that reserves are sitting idle and are not lent out by the banks, but this is simply nonsense. Mr. Stella rightly notes that reserves can only be lent and borrowed between banks in the interbank market.

As an aside to this, in China required reserves are actually a major component of the PBoC's monetary policy tool box (it uses them to regulate the extent of domestic monetary inflation that results from its foreign exchange rate manipulation and reserves accumulation), so the importance of reserves is not the same everywhere.

However, Stella's deliberations regarding bank reserves lead him down a theoretical garden path, as his following comment reveals. It seems to us that he comes to an absurd conclusion mainly as a result of conflating money and credit (hence the importance of properly defining money):

"There is a great irony in the journalistic history of monetary policy. What many are calling central bank "money creation" "helicopter money" or "rolling the printing presses" may – in combination with tighter leverage ratios – lead to a tightening of bank credit and deflationary pressures. And all this is occurring while the spectre of uncontrolled credit expansion and monetary debasement are being decried countless times by those who have not recognized that yesteryear's monetary paradigm is defunct."

(emphasis in original)

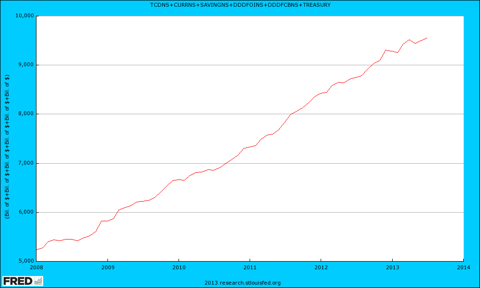

We thought we had heard everything, but this is the first time we have been informed that money printing might actually create deflation. It is no doubt true that tighter leverage ratios will have an impact on future bank credit creation. However, although bank credit expansion has almost screeched to a halt this year, the money supply has continued to inflate at a rapid pace. The broad true money supply TMS-2 is up more than $500 billion over the past year, 81% since 2008 (having risen from $5.3 trillion in early 2008 to about $9.5! trillion! today) and up around 230% since the year 2000, when it stood below $3 trillion. In recent months US money supply growth has actually begun to re-accelerate once again (as the quarterly annualized growth rate has increased relative to the year-on-year growth rate). The term deflation describes a shrinking, not a growing money supply.

(click to enlarge)

Broad US money supply TMS-2 since 2008: from $5.3 trillion to $9.5 trillion - click to enlarge.

How and Why the Money Supply Grows

Regardless of the existence of the 'shadow banking system' (i.e., various non-banks that are involved in credit intermediation), there are only two ways in which additional money can be created ex nihilo in a fractionally reserved fiat money system: either via credit expansion on the part of commercial banks, or directly by the central bank. Non-banks cannot create money. The process by which commercial banks create money is indeed linked to concomitant credit creation: only when banks make new loans are new demand deposits created from thin air.

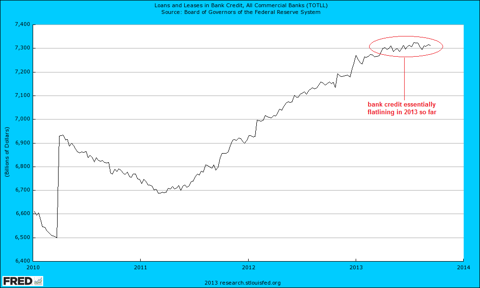

However, as we have seen, money supply growth has continued at a vigorous pace, in spite of the fact that bank lending has actually nearly flat-lined so far in 2013:

(click to enlarge)

US Banks, total loans and leases – almost no growth in 2013 to date – click to enlarge.

So why has the money supply continued to grow and by what mechanism has it done so? The Fed buys securities from the so-called primary dealers. When the sellers of the securities are banks, only bank reserves are created and no addition to the money supply occurs. However, when a non-bank third party sells securities through a primary dealer to the Fed, then both additional bank reserves and an equal amount of additional deposit money are created! .

M! r. Stella himself mentions further above that the account of the seller is credited by the commercial bank, but apparently doesn't think the implications through any further. Deposit money created in this manner is a perfect money substitute – the only respect in which it differs from the bulk of deposit money commercial banks normally create by lending is that it is 100% covered by bank reserves.

QE therefore increases the money supply – and an increase of the money supply is the very definition of inflation.

Mr. Stella seems to imply that only the 'release of collateral' from the Fed's balance sheet will reignite the inflation of money and credit by the private sector. We believe that quite on the contrary, a cessation of QE by the Fed would strongly increase the probability of outright monetary deflation. He is certainly correct that more stringent capital requirements and tighter leverage ratios due to new banking regulations are likely to keep banks from expanding credit (for a while, anyway). Moreover, the household sector is still deleveraging, and even though this is more than outweighed by government and corporate debt growth, it represents a headwind with regard to credit demand.

The 'shadow banking' system may indeed, as Manmohan Singh has put it, serve to 'lubricate' the financial system with its vast collateral chains of re-hypothecated assets. A smooth functioning of this system likely does lower the demand for money. However, the decline of the collective balance sheet of the shadow banking system is a result of the crisis, not of QE or a 'lack of collateral'.

We would in fact argue that without QE, the process of system-wide deleveraging would already have progressed much further and a lot of unsound credit would have been purged from the system. Instead, the money supply has been massively inflated and new asset bubbles have been created in the process. Judging from recent events, the Fed is now in a box of its own making – it did not even dare ! to slight! ly reduce the pace of QE at its September meeting, in spite of widespread expectations that it would do so. The financial system as a whole appears extremely fragile and like a drug addict, has become dependent on continual monetary pumping. We certainly would agree with Mr. Stella that QE has done a lot of economic harm an continues to do so – but certainly not because it is an obstacle to inflation.

Charts by: Federal Reserve of Saint Louis Research

Source: Money Matters

No comments:

Post a Comment